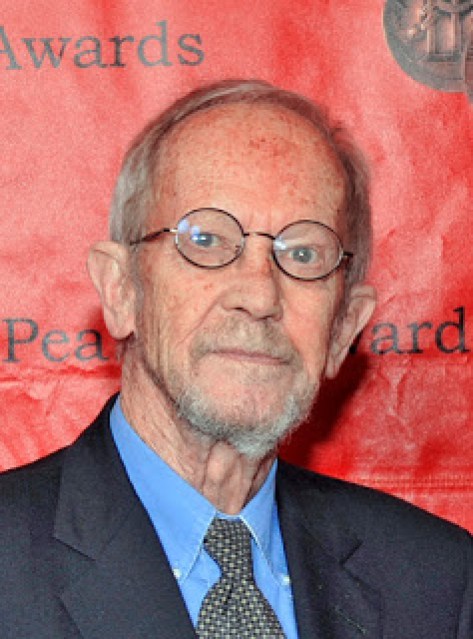

Elmore John Leonard, Jr. (October 11, 1925 – August 20, 2013), or Dutch as he was known to his many friends, was an American novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter. He began his writing career in the early 1950s writing Westerns, but went on to specialize in the crime and thrillers genres. Many of his books have been taken up by Hollywood and turned into movies. His best-known works are probably Get Shorty, Out of Sight, Hombre, Mr. Majestyk, Glitz and Rum Punch (which was adapted for the screen as Jackie Brown).

Leonard was a compelling writer and had his own set of 10 rules for how a piece of fiction should be handled. Here they are:

1. Never open a book with weather.

This is a strange one and I’m not quite sure why Leonard put this first. It is quite possible that it just reflects his sense of humor. On the other hand, beginning a book with the weather would almost certainly postpone the introduction of both dialogue and action, so it makes sense not to delay the book by getting involved in some tedious aside from the get-go about how it was raining or snowing. Sometimes people say that in certain works of fiction the weather is such a big factor that it becomes like a major character in itself. Even so, beginning a novel with weather is a very dangerous business and because you run the risk of turning the reader off straight away and they might just throw the book aside and never read any further. In a novel or short story you want to grab the reader from the very first words, introduce the main characters as soon as possible and get the action off to a flying start.

2. Avoid prologues.

I guess the same applies to beginning a book with a prologue. It can delay the substance of the book. For that reason, you could argue that if what you say in the prologue is important, why isn’t it contained within the body of the book. Similarly, if it is key information that you want to get across, isn’t it better to include it as dialogue from some of the main characters, rather than talking directly to the reader to explain it beforehand? And if it’s not very important information, then why have it at all?

3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

This seems to me good advice. In older novels, you quite often find characters “expostulating,” “ruminating,” or “exclaiming” dialogue. But equally, how characters say something can distract from what they are actually saying. “Said” is unassuming, incidental and doesn’t get in the way of the dialogue. In any case, you can convey a character’s attitude by adding little descriptions like, James did a double-take. “What the hell?” he said, rather than meddling with “said.”

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said”…he admonished gravely.

This follows the same rationale. There is also the possibility that if you use a lot of adverbs you begin to draw attention to the way in which a passage is written rather than what it’s actually saying. And that means you are beginning to disrupt the rapport you have with the reader and break the spell that you have put a reader under as they become absorbed in your novel.

5. Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.

This makes sense if you want to be taken seriously by the reader. Using exclamation marks sparingly, if at all, ensures that you maintain a certain gravitas or cool as a writer. It makes you more reticent as a writer, which is a good thing because you want to be as inconspicuous as possible. You want your readers to become absorbed in the action, and exclamation points can destroy that absorption.

6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This seems to me to typify Elmore Leonard’s writing. It’s low-key and unassuming. He lets the characters drive the action and, rather than commenting on it himself, he prefers to let his readers fill in the emotional blanks. Apart from the fact that “all hell broke loose” is a cliché in itself and therefore should be avoided for that reason alone, “suddenly” also has that sense of the writer commenting on the action rather than letting it develop naturally from the characters interactions.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Regional dialects are difficult to convey successfully, partly because they are difficult for the reader to understand immediately. In a novel or short story, the higher the profile of the character using the dialect the more regional language you end up using. Accents and patois place an added strain on the reader and force the reader to work fairly hard to understand what a character is on about. In the end, the reader might just give up, throw the book across the room and turn to something less intellectually challenging, like TV.

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

I quite often marvel at some writers who like to give detailed descriptions as each character appears. It is usually pointless, since the important thing about character interaction is what they say rather than how they look. The only exception is if you want to make sure that readers don’t confuse two characters. But then, you’re not really giving a detailed description so much as pointing out the characters’ distinguishing characteristic.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Again this is typical of Leonard’s style of writing. In fact, if you read any of his books, you realize that he prefers to begin a scene with dialogue and let the reader gradually intuit where the characters are from hints embedded in the prose or in the conversation. On the other hand, if the place or thing in question is key to the plot, then some description is almost always required. But good writers can sum up places and things with an economy of words, such that no detailed description is necessary.

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

Isn’t this the ideal description of a “page-turner”, a book that the reader is compelled to read because it has captured his or her interest and where one incident leads to another. The parts that readers skip, in fact, are usually detailed descriptions of places and things (see point #9). If you have written a novel and are now editing it, mostly what you want to do is cut out or rewrite passages that are irrelevant to the plot. To do that well, you may cut out so much that you end up with a novella rather than a novel. So be it. The work will be much more readable and better reviewed for the excision of padding, fillers and pointless explanation of people and things that are not key to the plot.

And here is Elmore Leonard’s final point and his most important rule, one that, in fact, sums up the previous 10: “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”